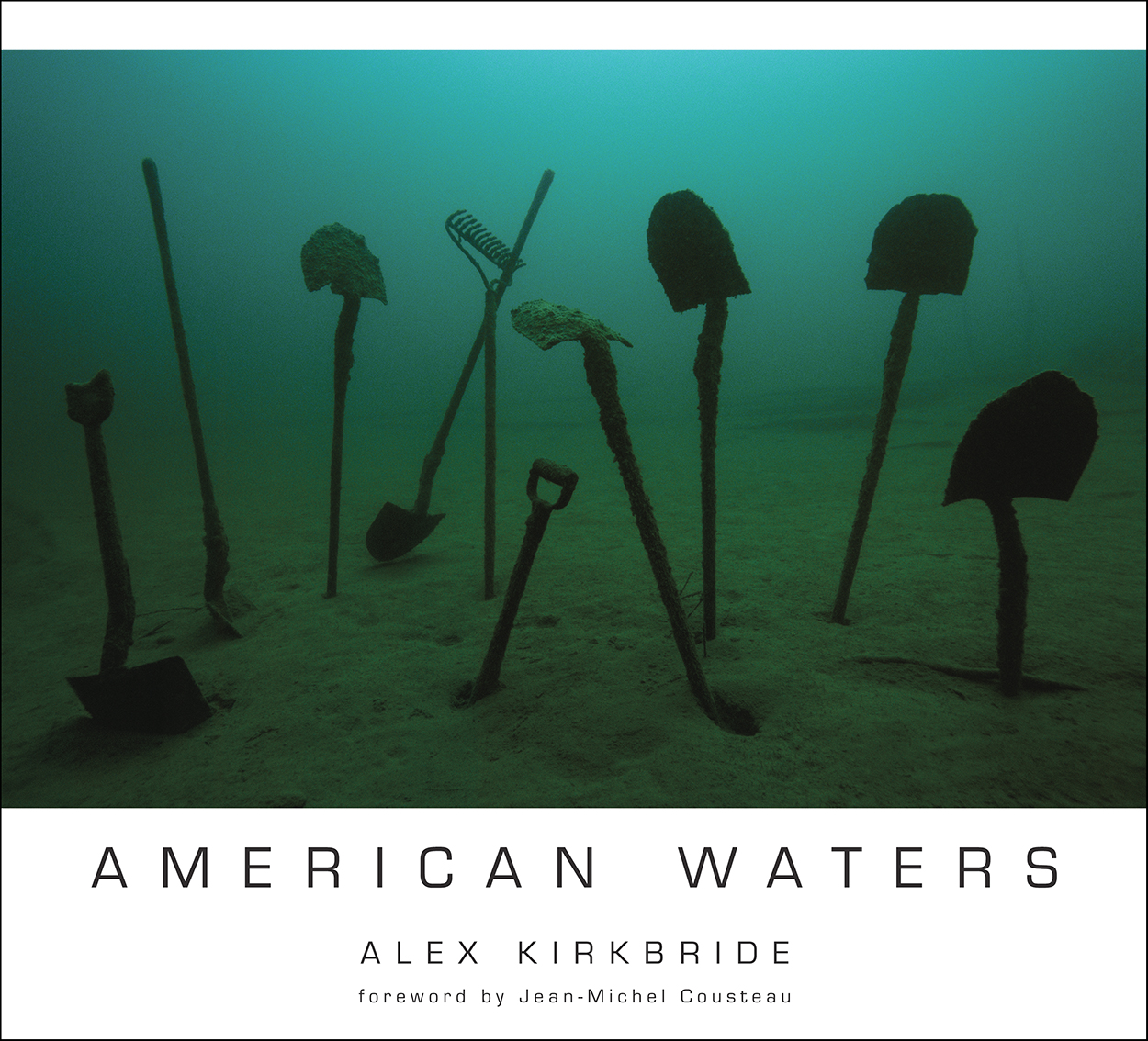

In 2002 Alex Kirkbride decided he wanted “an immense creative challenge”. He set out on a three-year journey across the United States with his producer and partner Hazel Todd, living together in an Airstream trailer and travelling 108,000 miles to photograph underwater images from every state. The result is a collection of 150 imaginative photographs depicting the amazing variety and astonishing beauty of underwater worlds unseen by most people in their lifetime.

“He uses boundless imagination and a keen eye to peel back the surface and expose a world that is beautiful, bizarre and wonderfully unexpected. …A new and very surprising view of America, from the bottom up.” David Doubilet

ABOUT THE PROJECT:

From flooded quarries and cranberry bogs to freezing Alaskan waters and Elvis’s swimming pool, Alex captured a unique array of photographs. His creative approach and unerring technical ability enabled him to make startling images – including the rare sight of a whale placenta and eerily still and beautiful wreck shots.

The photographs in the book are accompanied throughout with a compelling account of this American odyssey: the landscape, the challenges of non-stop driving and diving (he entered the water 945 times for a total of 732 hours in 848 days), the hazardous weather and the memorable people encountered along the way.

“Although this book is entitled American Waters, it speaks far beyond borders… Alex has pushed us to appreciate all water on Earth, no matter how simple or small. He dares us to think outside categories, labels, or convention. He has reinvented the medium and we thank him for that.”

From the foreword by Jean-Michel Cousteau

“The difference between a journeyman photographer and an artist is that an artist has a different way of seeing things. That’s a trait Kirkbride shares with such masters as David Doubilet and Douglas Faulkner.”

Eric Hanauer Wetpixel.com review

“An attention-paralysing, unique underwater adventure with spectacular, inspirational images. Surely a new benchmark in photographic originality”

Digital Photographer magazine book review

EXCERPTS FROM THE BOOK’S INTRODUCTION:

In July 1997 Aqua magazine commissioned a Diving Across America story. My assistant Sebastian, the writer Jim, and I travelled 4000 miles in nine days in a motorhome from Long Island, New York to Los Angeles, California. It was a gloriously mad, intense shoot and I’ve never been more exhausted after a job. For example, in one day I photographed the Sheriff of Santa Rosa, New Mexico, went diving in the nearby Blue Hole and adjacent creek, and then drove 900 miles to Las Vegas, Nevada. We arrived in Vegas at 1am and were up and moving by 6am. Then we drove to the Colorado River, went diving in an 8-10 knot current, and afterward flogged on all the way to Santa Barbara, California. I feel tired just thinking about it.

The results demonstrated how extraordinarily diverse underwater images could be. There was an impressionistic image of a cottonwood tree from New Mexico, an antique dentist’s chair from Indiana, and an ore cart from a flooded mine in Missouri. I began to think about what else I might find on a lengthy trip around the country and how it might make a unique collection of images – a portrait of America from a fish’s point of view, or a crocodile’s, or a turtle’s eye in a desert spring. It would be an enormous challenge to capture images expressive of American waters from coast to coast – a feat no one had ever attempted before…

Any body of water was fair game, so the quest for images led to diving and snorkeling in the most bizarre places, especially when it came to fresh water. Rivers, creeks, streams, lakes, springs, marshlands, caves, swamps, and wetlands were all explored. The expedition went to the source of the Mississippi River in Minnesota, and I even lay in a puddle in New York City. In Massachusetts at harvest time, I jumped into a flooded cranberry bog – cranberries being one of the few truly native fruits in the USA – to the great bewilderment of the farmers. For Kansas, when the time came to photograph cattle in some aquatic situation, I spoke to my friend Rob, the only person I knew from the Heartland State, the geographical centre of the contiguous United States. Rob’s father put me in contact with a rancher, whose foreman didn’t think my notion too far-fetched – until I asked to jump into the cows’ water tank.

In the vast swamplands of the south, I slipped into murky waters knowing there were alligators around and imagining them whenever my leg brushed up against a submerged tree trunk. But you force yourself to control those thoughts; you have to, in order to concentrate on the task at hand.

Somewhere in the Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge in Louisiana, I broke this mental barrier, and sharing the water with lurking near-relatives of the dinosaurs became less of an anxious experience and more of an exhilarating one.

From the beginning of the journey, one of the greatest challenges was what could be created in Nevada, the driest state in the union. Research had turned up Stillwater Marsh, where you can see the occasional sand dune from the water’s edge. However, a five-year drought had all but dried out the shallow marshland. Instead, we found copious amounts of buffalo carp bones lying where those fish had gasped their last breaths. We spent the entire morning driving around in search of an acceptable body of water and almost ran out of gas – a near-disaster that made us think again about those fish bones. By that point, Pyramid Lake in the Paiute Tribe Reservation seemed my best chance, and the most I expected was a split-level image of Pyramid Rock. Instead, a fortuitous meeting with a fisherman led us to some dramatic underwater tufa formations, and four days later we left the desert with Nevada in the bag, much to my surprise and delight.

Perhaps some of the most unique water in America can be found in Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first national park, founded in 1872.

Yellowstone is home to some 10,000 hot springs and geysers, including Old Faithful, possibly the most famous fountain in the world. Now you can’t just jump into these areas-you aren’t allowed-and even if you were, you’d find yourself being boiled by the world’s biggest Bunsen burner, the Yellowstone Caldera, the giant volcano that lurks beneath the parkland. There was another option, however, and one that was both very cold and very hot: Yellowstone Lake. Protected from the snow-melt chill by a drysuit, you can dive down to bubbling geothermal vents where there are also clusters of spires, and some very odd growths of green algae the size of 1960’s beanbags.

My dives in the high-altitude lake, where I felt the Earth shake with subterranean thunder, were unforgettable, and humbling. To dive in such unusual places, where few if any had been before, was one of the greatest joys of the journey. Alex Kirkbride